180 countries. Hundreds of products and services. Thousands of designers and engineers.

At that scale, ensuring consistency in design is brutal, but vital.

Enter the Citi Design System (CDS) Team, which governs design, development, and usage of reusable design components, like Accordions, Dropdown Menus and the like.

As the team's sole writer, I wrote guideline documentation for all of said components. Here, I've curated sections from two widely used components to demonstrate my approach to standardizing guidelines for designers and developers across the globe.

Really into guidelines?

See the full versions of these and other guidelines I wrote here:

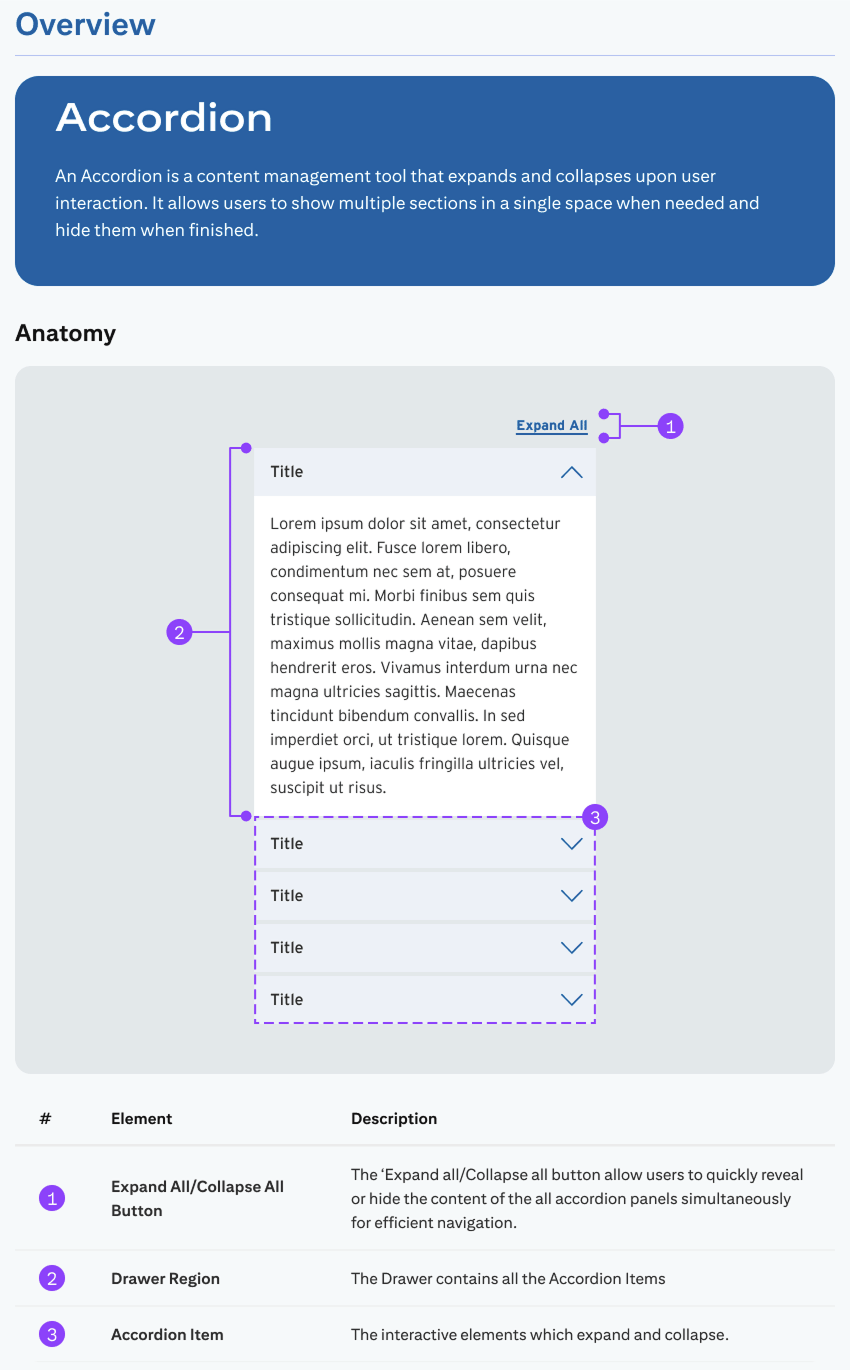

Rather than treating the Accordion as a purely visual component, I defined it as a content-management pattern with clear linguistic hierarchy.

Establishing this foundation early prevents misuse, reduces ambiguity, and ensures that expandable content behaves predictably across Citi’s global product ecosystem.

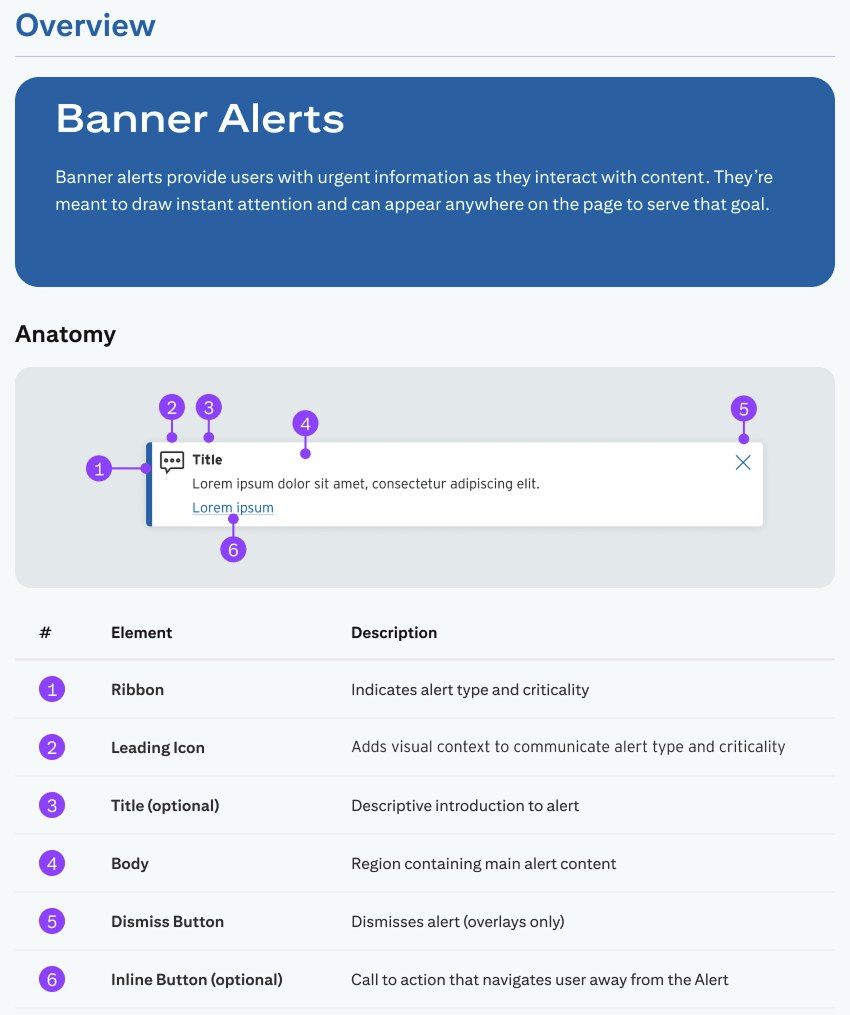

This opening section displays the component in an expanded view and labels its anatomical components.

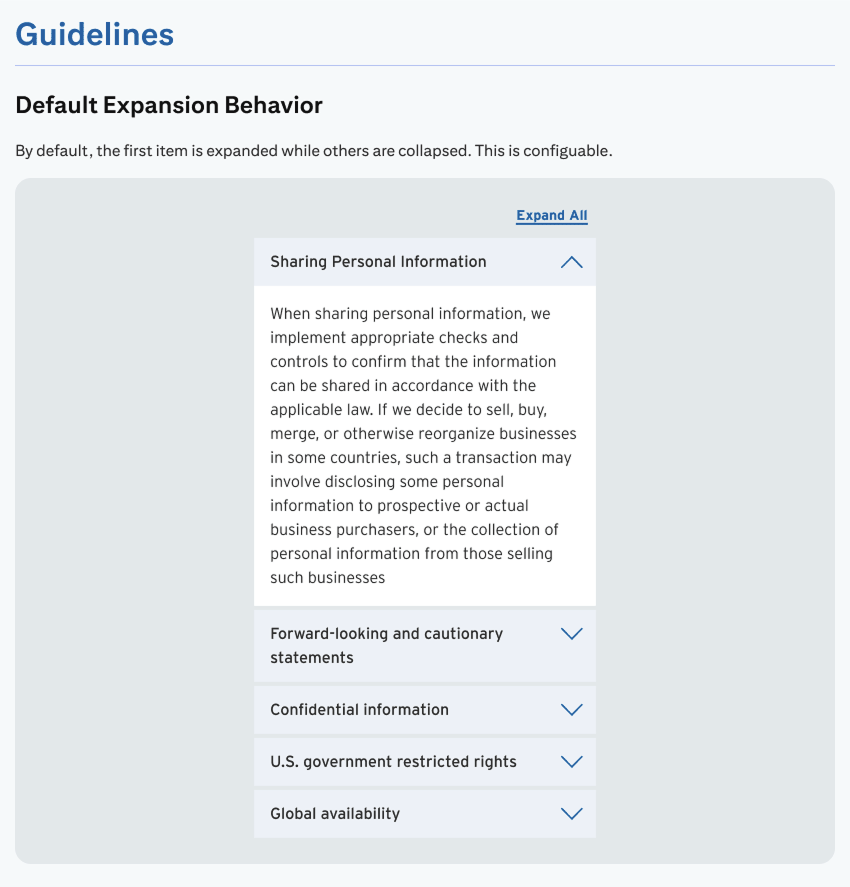

Now, the nitty-gritty—where the guidelines start getting technical.

The CDS Team fielded constant questions about the Accordion component from other design and development teams, specifically, regarding the default expansion behavior. My guidelines were a direct effort to alleviate that.

To be fair, important UX considerations went into defining expansion behavior. Opening the first Accordion on page load reveals some initial content, and also indicates the others can expanded at will.

My design partner and I created clear visual instructions for this behavior, which vastly alleviated meetings with other design teams.

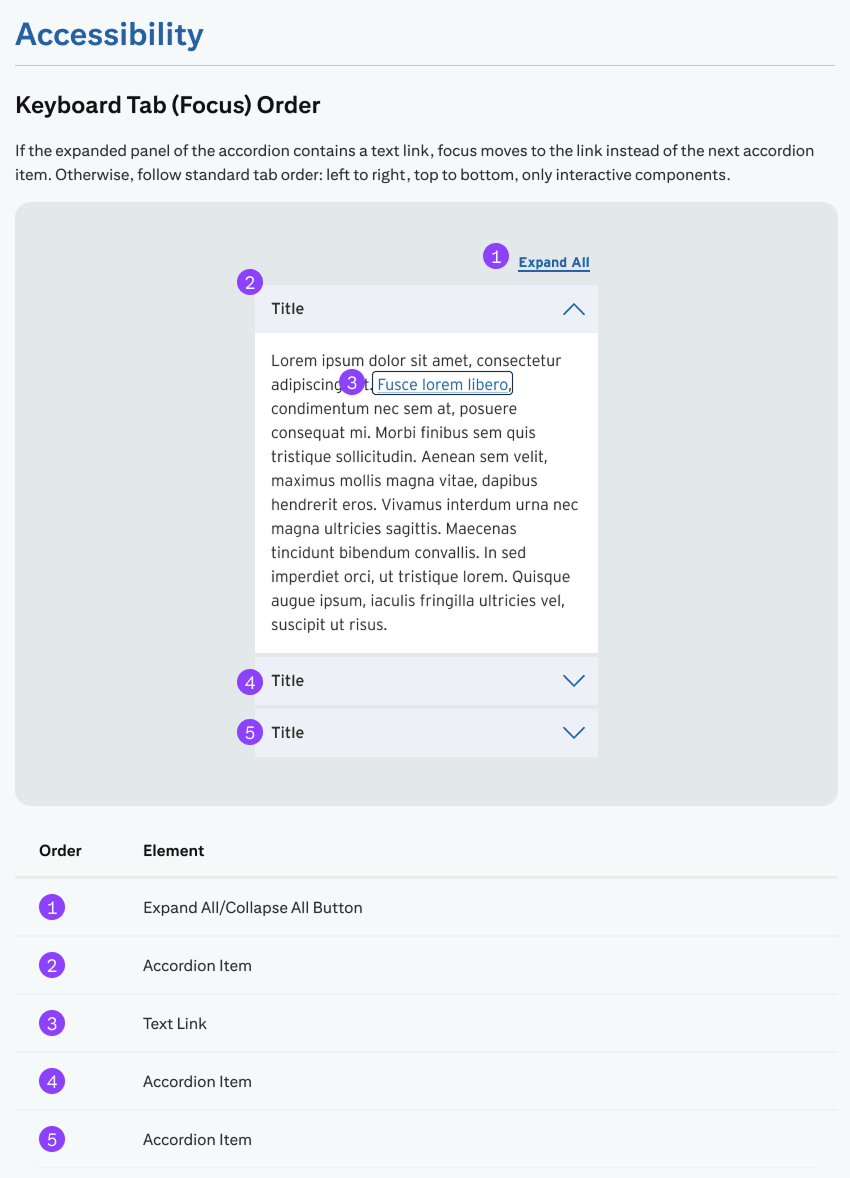

During in my time with CDS, Citi was hit with an eye-watering fine for noncompliance with several (ADA) requirements.

So, naturally, we added an "Accessibility" section to our design guides.

At a component level, accessibility involves two things: how assistive technologies announce interface elements (ARIA labels, semantic structure), and how users navigate interactive elements using the keyboard.

Because most of the content within this component is live text, I highlighted keyboard tab and focus order for non-visual and keyboard-only users.

The Banner Alert component was one of our more technical and frequently misused components, which is why I chose to highlight it.

Here you can see the basic anatomy of a single Banner Alert. Behind its simple, minimal layout sits a complex set of rules governing tone, severity, placement, and user interruption—each of which has real consequences for trust and comprehension.

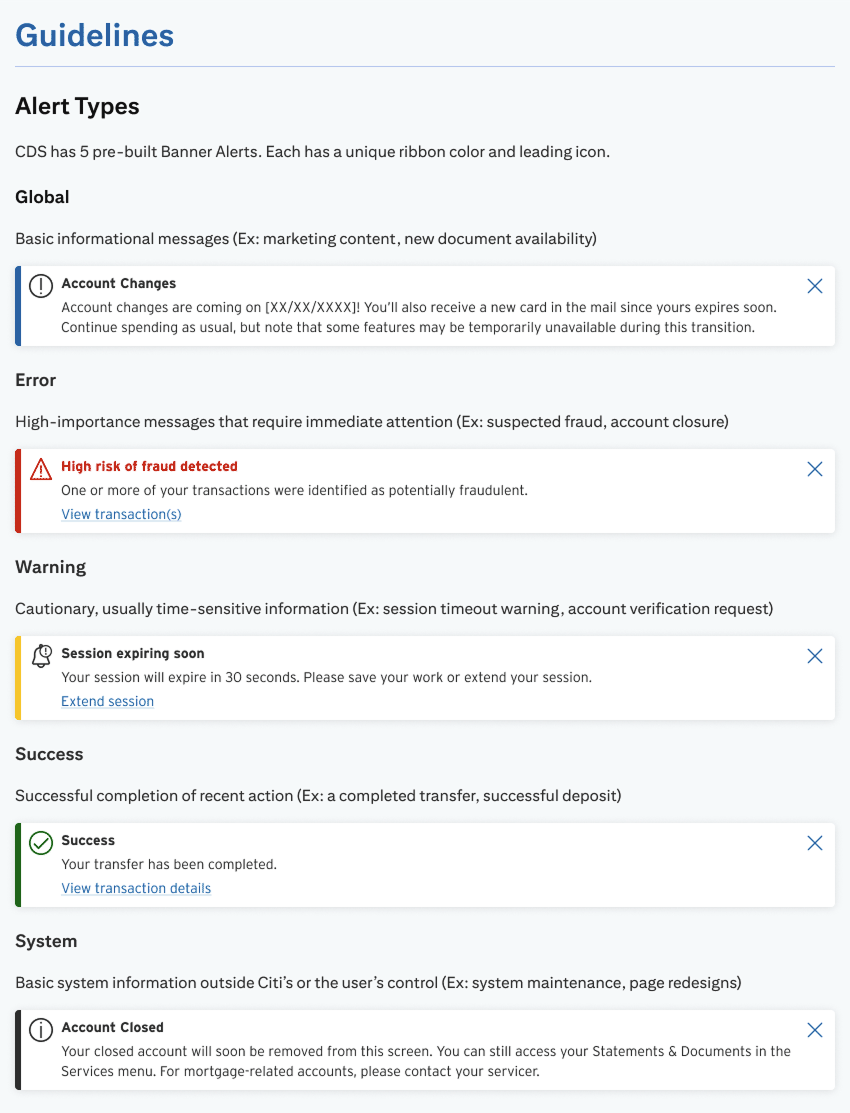

The first trick to writing usage guidelines for Banner Alerts was giving them distinct (and succinct)names. This was a requirement from developers.

But they couldn't just be any names—they had to accurately describe the individual Banner types' content and use, which was a challenge given some seemingly trivial differences between them.

Take the "Warning"and "Global" types, for instance; our team pushed to combine them, but our developers correctly pointed out edge use cases making that impossible.

All this to say, defining when and how to use the Banner Alert types was a real challenge, but by directly facilitating communication between our design team and developers. And I got it done.

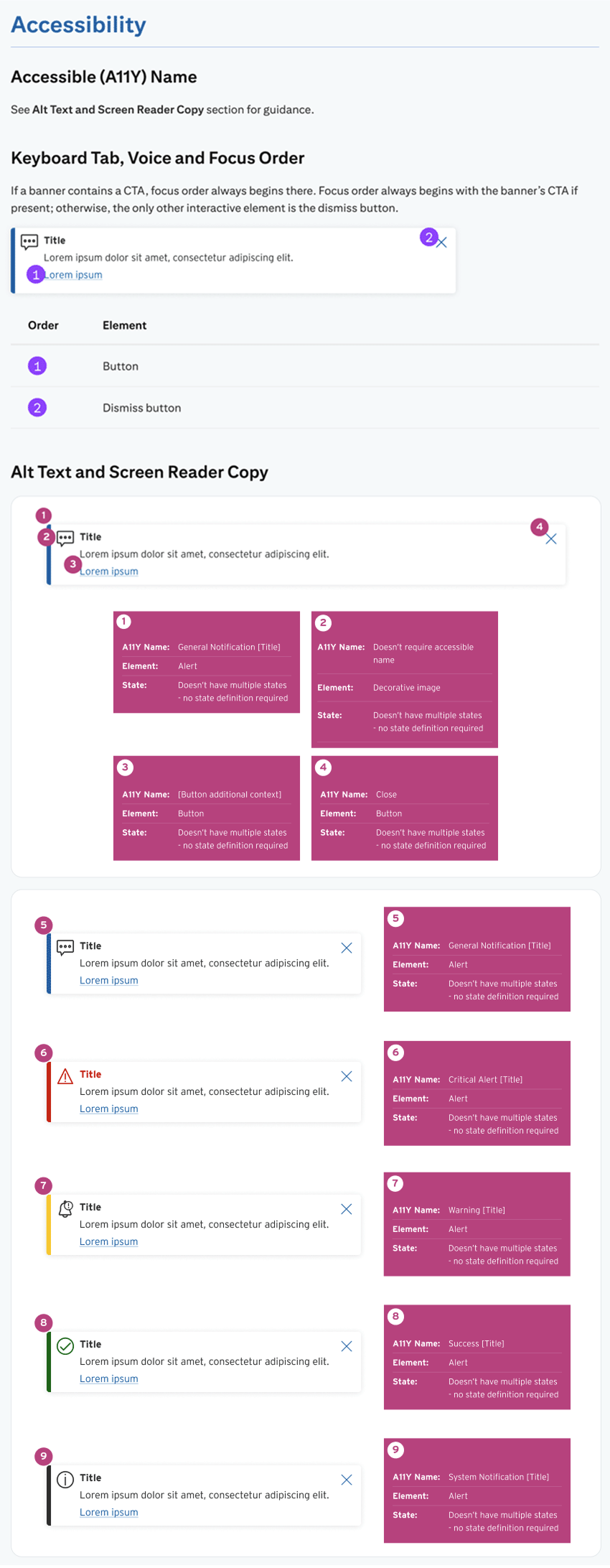

Citi's Banner Alerts rely on color and iconography to convey message urgency, which is obviously unacceptable for unsighted users. This made defining and explaining the component's accessibility functionality one of the most challenging parts of the project, but arguably the most important.

I had to define a unique ARIA labeling system that would allow assistive technologies to:

Plus, since the Alerts support both dismissal buttons and CTAs, I had to design a customer focus order that allowed disabled users to select the CTA first, if needed, instead of dismissing the Alert altogether.